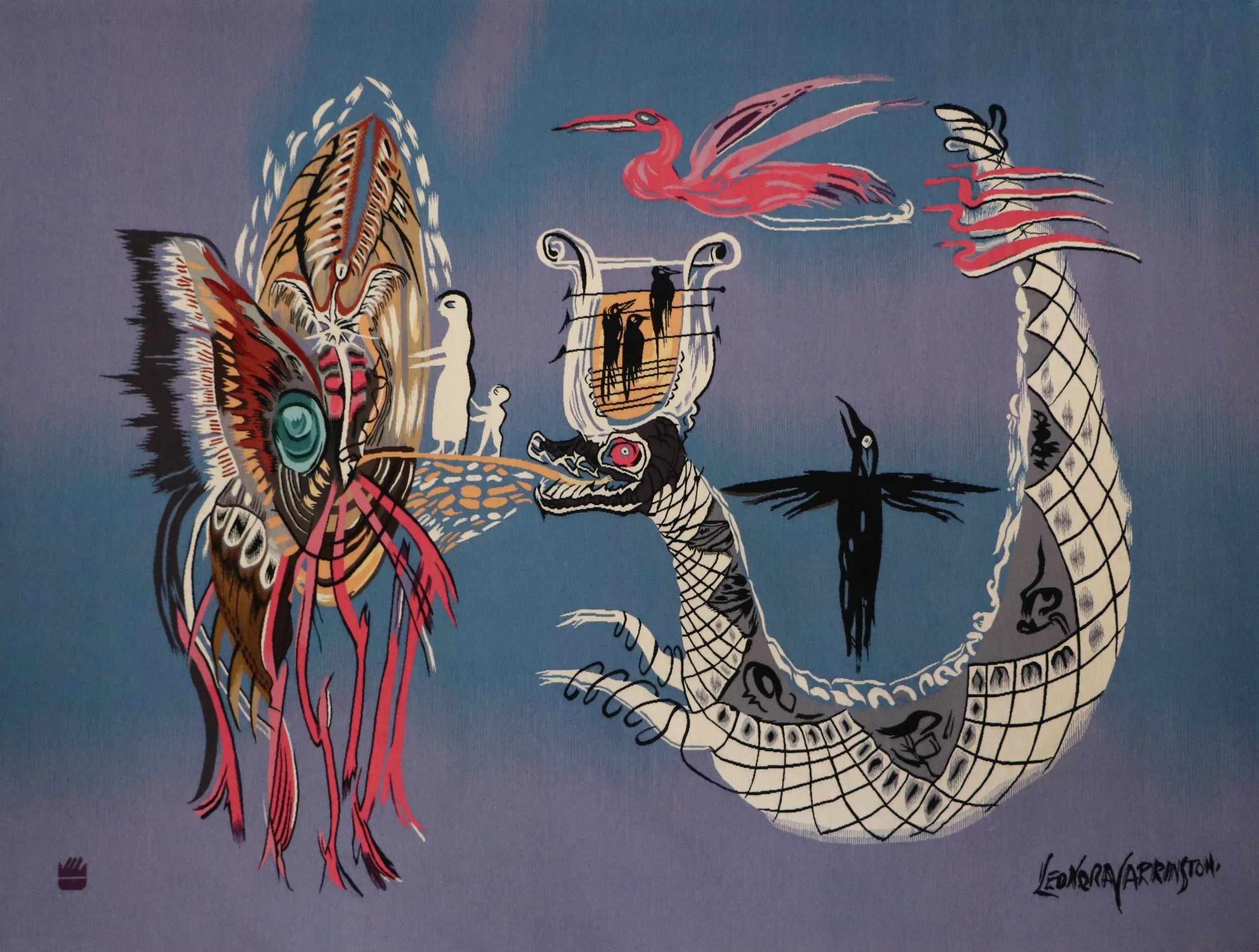

'I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse… I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.'

'Woman with Fox', 2010

In 1937, Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst met at a dinner party. The scene unfolds with a 47-year-old artist meeting a beautiful 20-year-old fan yearning to disrupt the status quo.

Their connection was instantaneous, a magnetic pull that defied societal norms. Leonora, restless and spirited, choses to leave behind her family's expectations, eloping with Max to France. Together they go to Paris, where she is introduced to the the main figures of Surrealism, including Jean Arp, André Breton, and Yves Tanguy. Leonora and Max settled in Paris at rue Jacob, not far from Pablo Picasso’s house, and then moved to Southern France, where they lived carelessly until the beginning of World War II.

'Leonora and Max'. Paris, 1937, by Lee Miller

During their time together, Leonora’s eccentricity became legendary.

She famously served 'hair omelettes' at parties, made from guests' own hair she had cut the night before. Far from her stifling aristocratic family, she started honing her distinctive style, which later became populated with mythical beings set in dreamlike surroundings—a world rich with symbolic undertones yet resisting clear interpretation.

“Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse)” (1938), Carrington’s first major painting, completed while she was living in France with Ernst.

At the outbreak of World War II, to avoid capture by the Gestapo, Ernst had to flee Europe with the help of Peggy Guggenheim. He left Leonora behind and later married Guggenheim in 1941.

After the war, Leonora traveled to Mexico, a country André Breton called "the most surreal nation on the planet," where she eventually emerged as the visionary surrealist we recognise today.

'The House Opposite', 1945

However, to grasp the enormity of Leonora’s decision to relocate all the way to Mexico, one must first reckon with the life she abandoned in France.

A Europe in turmoil, consumed by war. She endured months in a Spanish asylum—where she was forcibly restrained and drugged—a harrowing escape to New York, and of course the shattering betrayal by Max Ernst, the man she once believed was her forever. Although they would cross paths again in New York, their relationship was luckily never reignited.

Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, Andre Breton, New York, 1942, by Hermann Landshoff

'Green Tea', 1942

'Tuesday', 2008

Later, Leonora fell in love with Hungarian photographer Emerico "Chiki," with whom she had two sons. They remained together for six decades until his death. She spent the rest of her life in Mexico, becoming an iconic Surrealist painter and a key figure in the Feminist movement.

To those close to her, she was warm, witty, and disarmingly genuine. But interviewing her carried the risk of a sharp rebuke. She refused to explain her work, often stating, 'Nothing to explain!' For her, intellectualising about art was a waste of time. In her final years, although accolades poured in, they meant little compared to the love she had for her family and friends. She lived a rich and fulfilled life, remaining fiercely true to herself until her last breath at the age of 94.

Lancashire, 1917– Mexico City, 2011